Gwalior Fort: Where Majesty Meets Mystery

Man Singh Palace: A Kaleidoscope of Beauty and Betrayal

Babur, in his Baburnama, describes the fort of Gwalior as a "pearl amongst fortresses of the Hind," a sincere compliment from a nomad king who was trying to find a foothold beyond the Indus. The adventurer from Ferghana was awestruck by the fort’s magnificence and impregnability.

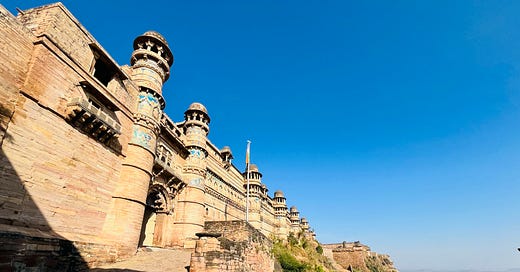

Five hundred years later, the fort still manages to leave visitors speechless. As you begin the ascend from the Kila Gate, the fort gradually unveils itself. It is a visual crescendo that reaches its zenith as you make your way through Hathi Pol (Elephant Gate).

This is where one finds the Man Singh Palace—a symphony of turquoise tiles, latticed screens, and ochre walls that echo tales of power, ambition, and cruelty.

The palace, constructed in the late 15th century by Raja Man Singh Tomar, was a bold statement of grandeur and defiance. Man Singh, the ruler of the Tomar dynasty, envisioned the structure as a symbol of his kingdom's cultural and political zenith.

Completed around 1508, it served as both a royal residence and a public proclamation of the Tomars' artistic sophistication. The architecture bears influence of Hindu styles, interwoven with Persian aesthetics, a reflection of the region’s cosmopolitan ethos. Its blue-and-yellow ceramic tiles, geometric motifs, and ornate carvings were crafted to awe visitors.

Walking through the palace, one is struck by its labyrinth of rooms, each with a specific purpose. The zenana, or women’s quarters, with intricately designed jalis (lattice screens), ensured privacy while allowing the women to observe life in the courtyard below.

The music halls resonated with the sound of the dhrupad style, a classical genre pioneered under Man Singh’s patronage. The palace’s strategic position on the hilltop afforded it a natural defense, with its high walls and narrow passageways designed to thwart invaders. No wonder the British called it the ‘Gibraltar of India’.

Yet, beneath its veneer of beauty lies a darker narrative. Deep within the palace’s subterranean levels are chambers notorious for their grim purpose: torture. These dim, airless rooms bear silent witness to the cruelties of the era. Their walls, rough and stark, contrast sharply with the opulence above.

One such chamber is etched into historical memory. During the Mughal conquest of Gwalior, Emperor Akbar turned the palace into a prison for political dissidents. Among the notable figures confined here were Akbar’s cousin Kamran, who was blinded and later executed, and Aurangzeb’s brother Murad, who met a similar fate.

Takht ya taboot (throne or the coffin), was a common theme during the rule of the Mughals, like all other dynasties before and after them. The chambers held princes, once symbols of power, as they faced the brutal realities of imperial ambition and familial rivalry. Their tragic ends serve as reminders of the human cost of empire-building.

As I stood in one of these chambers, the air seemed heavier, carrying the weight of centuries of human suffering. The dim light from a single crevice in the stone wall illuminated the starkness of the space.

The silence oppressive, broken only by the echo of my footsteps. Here, history whispered its truths, raw and unvarnished, urging me to remember not just the grandeur of Man Singh’s vision but also the shadows it cast.